The featured photograph at the top is of my grandparents’ farm in Winterport, Maine. They are at the very heart of my love for raising animals and growing plants.

This is a work in progress and will be updated as the seasons come and go like tides in Maine forever morphing seasonal landscape. Below is an outline for planning a complete working homestead garden for Maine’s climate. Each centered header breaks the seasons down. Under each season are mini-sections with best practices, common tasks, projects and tips in each section. For me, planning a garden for Maine’s climate never starts or ends—it is a cycle. But this post has to have a place to start, so let’s start with ordering seeds in late winter.

Late Winter

Ordering Seeds & Plants

Ordering Seeds & Plants

As winter wears on seed catalogues begin to arrive in my mailbox taunting my deepening case of cabin fever to surface. I chuck all the brightly colored flower and fancy bulb catalogues; they do not excite me. My garden space is limited and I’m all about utility.

I lived in an apartment with daylilies out front once and my neighbor pointed out how my plant budded but had not bloomed much. I laughed and told her it was because I’d eaten all the buds other than a few I’d left for the bees. They are lovely in a stirfry. She didn’t make conversation with me much after that and watched me closely as she watered her many bright mostly inedible flowers. I wondered if she suspected I had eaten them when deer did them later that summer.

To get the most of your order, you’ll need to first know how much you have space to grow.

- Growing space limits

- Full sun planting areas

- Available soil to plant in (more on this below)

- Yard size

- Starting seeds inside (counter space)

- Time requirements

- Weeding & Thinning

- Planting outside

- Starting indoors vs. buying plants

Required Space Estimates

Every year I have more seeds and plants than I know what to do with. Don’t underestimate how much room your mature plants will need when planting seedlings. Not all the seeds will germinate. Even if most germinate, some will do better than others and the weaker, leggy plants who don’t grow as fats ought to be wedded out of the seedlings early. This is especially true for folks who keep seed from their harvest to ensure a good solid strain.

With these things kept in mind, plant more seeds than you have room for when planning a garden for Maine’s climate. Accept that some will not sprout, others will not make the cut and if you’re lucky a few won’t fit because you’re thumb is so green. If you don’t have as many as you were hoping for when it comes time to sew the transplant, it’s okay—you can always cast a short crop like lettuces or bush cukes.

Starting Seeds Indoors

Seed packets will often have a germination rate, if yours doesn’t the days the seeds usually take to germinate can be easily looked up online or in the catalog they were ordered from. Germination depends on how happy your seeds are. A moist, damp environment without air circulation is best. My plant science teacher would have us fold them a wet paper towel and slide them into a sandwich bag that was labeled with the date and plant name.

To have less of an environmental impact, I place my germinating seeds in a cloth then place them under wax paper with some small rocks to hold the corners down. I set this mess onto a cookie sheet or other flat. I have a lot of big wire dog cages and use the flats out of those too. This method is especially good for seeds with thick, woody hulls. Some seeds will benefit from scarification—which is a silly word for scratching up the woody hull of the seed. When a seed is scarified, it will imbibe water. Imbibe is a fancy word for sucking up water

Once in the bag or wax paper, set them in a warm spot—near a wood stove, or on a shelf in the kitchen. There are heated mats made just for this called germination mats. They suck up a fair amount of electricity and aren’t necessary. I’m lucky enough to be running incubators this time of the year and have brooder boxes full of chicks indoors too. With all this added heat I have the perfect flat warm spots to germinate seeds. I just love multifunctional uses like this.

Once they are sprouted they should be carefully handled set in moist soil. Seedlings that have thin, smaller stems like lettuce will need to be sprinkled with a very light layer over soil over the top once set in moist soil. Larger, sturdier plants like beans, peas, and buckwheat can be covered with a thicker layer and pressed down lightly to remove any air pockets.

Once they are sprouted they should be carefully handled set in moist soil. Seedlings that have thin, smaller stems like lettuce will need to be sprinkled with a very light layer over soil over the top once set in moist soil. Larger, sturdier plants like beans, peas, and buckwheat can be covered with a thicker layer and pressed down lightly to remove any air pockets.

Recycled materials to save for plant pots include:

- Paper towel and toilet paper rolls

- Cardboard milk cartons

- Cereal boxes—keep the plastic liner

- Plastic oda and water bottles cut off where they taper—keep the top

- Feed bags from livestock grain

- Cans from food—use pliers to squish the little sharp piece flat

- Cardboard six-pack carriers—plastic bottles fit in them

Paper towel and toilet paper holders make great seedling starters. They will unravel and fall apart if not tightly packed and set in a tray with sides. The cardboard, like any other organic matter pot, will need to be peeled away from the plant roots before transplanting—even the ones advertised to be set right in the ground. These soft, organic matter based pots create a barrier to root expansion and can inhibit growth.

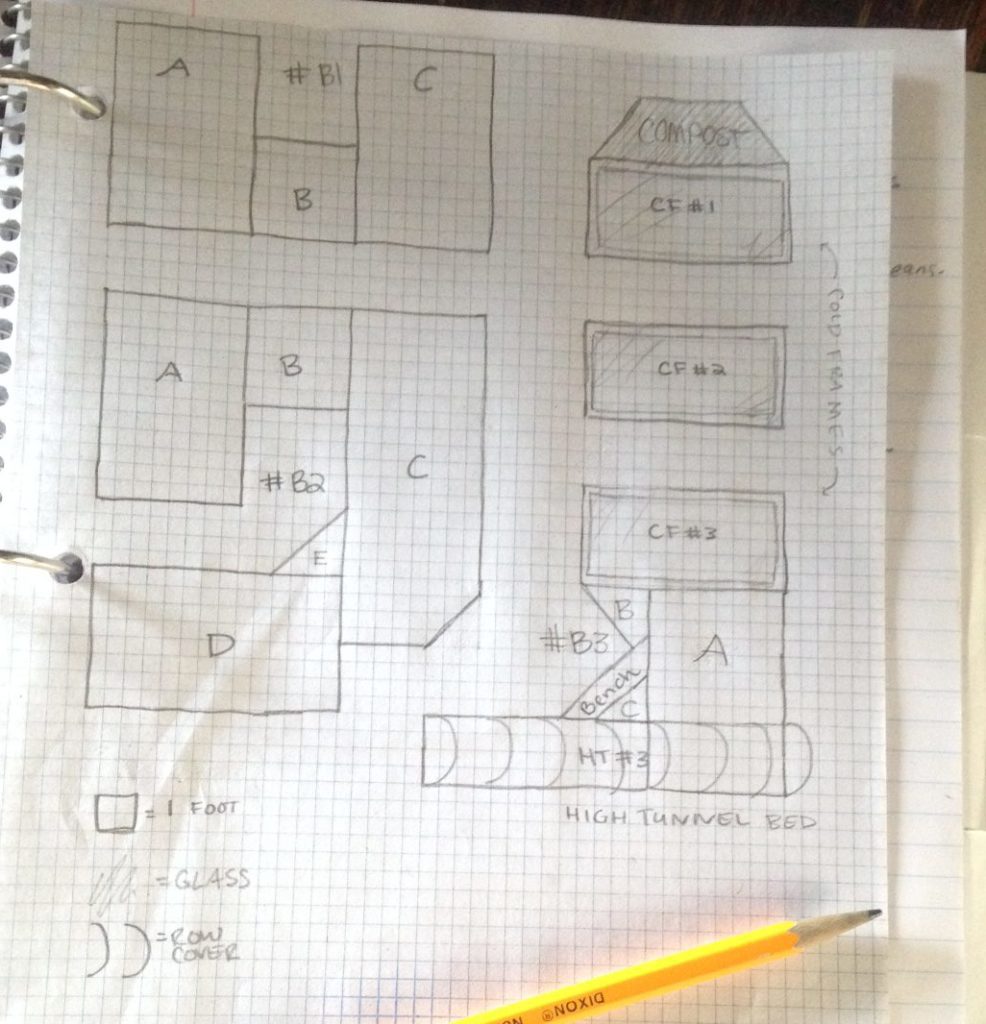

Layout Plans

Figure out how your garden will be set up. In Maine, winter is a log, hard endeavor. Wildlife, people, the plants and landscape all move slower and await The Big Thaw. While this icey period extends from November through April there lies a perfect opportunity to plan and prepare for the abundance that The Big Thaw brings. For more about planning in the winter months and how I keep busy, see this post.

Crop Rotation

Some plants need more, and different nutrients from the soil they live in than others. From one year to the next, and sometimes even during the green stretch from May through September I change up where things are planted. By putting the corn and beans in different places it keeps the soil from becoming depleted.

Risk of soil nutrient depletion can be decreased or avoided by consistent and persistent compost mulching and weeding. If your garden is as closely planted and heavily used as mine it needs some serious love to keep it in peak production. More weeds means competition for sunlight, water, nutrients and space for your crop. Mulching adds nutrients plus keeps the weeds down when done right.

Early Spring

Acclimating Seedlings

Acclimating Seedlings

So you made it to spring and didn’t go insane. Good for you! Hopefully you took good care of your plants and they were regularly watered and had enough sunlight. Once your beloved green babies are ready for transplanting when the frosts have passed and the soil is mucky but workable you can begin to acclimate them.

Bring seedlings outdoors on mild days when there is full sun and little to no wind. Set them in a cooler place in your home if possible. Set them outdoors a little longer each time. If you have a cold frame to set them in this can be used until night temperatures reach a consistent 40° or better—more about this in the section below.

Set out young seedlings once danger of all frost has passed—this is what most seed packets say. In Maine, this is hard to set and often a gamble.

When to plant out seedlings and to give them the best start:

- Look up historically when you, or other family gardeners have set them out in the past.

- Set a finite date (mid-May in central Maine) and watch the forecast

- Use sheets, plastic or koshes to protect your plants each night the temp is below 40°

- Wait until lots of other folks have set theirs out in your neighborhood.

- Watch the weather and local temps, wait for a several-day stretch of temps above 40° at night.

- Avoid putting them in the ground if there are high winds, driving rain, or dips in forecasted temps near 35°, or lower.

Using Cold Frames

A cold frame is an unheated boxy structure that plants can be kept or grown directly in. The top is clear to allow sunlight to enter for both photosynthesis and to trap solar heat. The bottom is directly on the soil to use the heat from the Earth to offset the changes in air temperature from day to night. It’s fully enclosed but can be lifted off or hinged to allow for easy access. I’ve made them from concrete blocks and a glass-panel screen door I found in a trash heap along the roadside.

Cold season plants thrive in cold frames:

- Beets

- Broccoli

- Cabbage

- Carrots

- Cauliflower

- Kale

- Lettuce

- Parsley

- Peas

- Radishes

- Spinach

To make them extend the season in either direction they can be better fortified, insulated or converted to be a hot bed—more on those later. For instance, you could build one by digging down into the ground three feet, setting hay bales all around then an old window on top. For a more permanent cold frame, build it from lumber with a double wall and fill between the walls with dried sawdust, straw, raked leaves or pine needles. Set a window over the top and hinge it—boom, you’ve got three more weeks in spring and in fall.

Soil Type

To find out your soil type and recommended soil amendments, you can take a soil sample and send it to the University’s soil lab. I took classes and worked briefly in the lab there. The soil is dried and measured for organic content. Once the organic content is removed the soil is then classified depending on the amount of sand, silt and clay in the sample. The lab will give a report of the soil type and recommend amendments depending on what you plan to use the soil for.

Maine’s official soil type is called Chesuncook and can be found in our characteristically acidic, relatively young forest soils with thin soil lying over granite bedrock. Much of our productive farmland in Maine is glacially sorted and deposited soils. Glaciers were covering Maine only 13,000 years ago. As these thick ice mats slowly slided back north and melted they eroded Maine’s mountains to rounded over, soft peaks, and deposited those soils in valleys and in snake-like ribbons along flat areas called eskers. These are well drained, mixed small grains and gravel often with large stones that need to be removed to make room for plants.

More recently water transported soils along floodplains near our largest rivers are both productive and generally free of larger rocks but will have heavier layers of grass that must be removed and tilled to use for as farmland.

Many areas that were once farmed have old pastureland grown into young forests and can be reclaimed with some work in removing trees. The good news is the stones have likely been removed, a key indicator is a nearby rock wall in an area with trees all of the same size. This is very common in Maine. Old wire can be found growing into trees that grew up over, around and through it as it was forgotten as time and technology moved on.

Our home is on the edge of a bog that has deep black muck under a layer peat moss. Alders line the edges, sparse tamaracks dot the vast open meadow of cattails planted firmly in the peat. Our miles-long view from the cabin of the sunny waving cattails is lovely, but we have many large mature pines and fir as the alders recede then maple, beech and poplar as the soil turns sandy and gravel laden. This mix is extreme, varying wildly across our 14 acres. A stream meanders through the meadow and woods on our property. The stream is lined with gravel beds, thick mossy banks, tall maples lean overhead and thick fir groves give shelter to partridge and wild turkey at night.

With a thin organic layer mostly made of coniferous needles, acidic muck, deposits of sand and gravel, larger cobbles in clumps underground wherever we dig and pockets of clay; it is near impossible to have a proper in-ground garden on our property. We would hate to disturb too many mature trees or impede upon our pristine view of the meadow. For some time I contemplated putting a deck out over the meadow to get sunlight and instal an extensive container garden out there. Instead, we have decided to drop a few choice trees that are leaning too close to our home anyhow and build a raised bed system with cold frames. This plan leaves all our mature maples up for tapping, reduces fall risk on our home by big pines, and make the issue of soils less complex.

Many considerations must be made in planning a garden for Maine’s climate and soil is high on the list. If your soil is lacking nitrogen, compost can be added. Each with it’s own pros and cons and some easier to come by than others. It’s best to use what you have on hand, is local or the cheapest.

Compost Types:

- Horse and Cattle Manure

- Pig Pen Rotational Planting

- Poultry Manure

- Fish Hatchery Waste

- Kitchen Compost

- Rabbit Manure

- Store-bought

Late Spring

Direct Sown Seeds

Many plants with short growth periods can be quickly and simply cast on the ground. Very small seed, like lettuce and carrot seeds are hard to sprinkle without dropping some to close one another. When plants are too close they will compete for resources and will need to be thinned for a highly productive crop. To remedy this issue, a salt shaker or old spice shaker can be used. Fill the shaker with sand and seeds mixed all up and slowly walk along the row or path to be seeded while gently shaking the seed and sand mixture. A fine layer of compost or loam can be sprinkled over and patted down.

Climbers and ground vines are usually planted in hills. These mounds should be a highly fertile mix as it will be difficult to reach the base of these plants after the large, supple leaves have taken over. I like to use rabbit manure for these hills, mixed in and on top to trickle in with rain. Rabbit manure can be used immediately unlike most livestock manure.

We have seven rabbits and are able to direct sow seed and transplants with rabbit manure. The tiny round turds are super easy to collect, store, handle and spread. Many cast-spreaders made for lawn seed will take rabbit droppings and cast them in a nice even manner. They are miraculous natural fertilizer pellets.

Companion Planting

This is a trusted method by a select few, and completely forgotten by Big Ag. Companion planting is to plant mint next to your beans to attract pollinators, pole beans to climb your cornstalks. This practise utilizes the properties of and form of individual plants. Companion planting is an essential part of planning a garden for Maine’s climate in my book for the below reasons:

Benefits of Companion Planted Gardens

- Larger plants protect smaller, more delicate plants from wind, erosion and sunscorch.

- Tall, strong plants can be trellises for others.

- Beneficial insects that eat garden pests and pollinate are attracted to some plants like mint.

- Pea/bean family plants draw atmospheric nitrogen and “fix” it into soil for use by nearby plants.

- Some plants emit odors that hide the small of vegetable plants from harmful pests.

A turnip grows a large round root at the base of a relatively small, low leafy top. Plants that grow deep roots but need more room above the soil wouldn’t interfere with the growth of the turnip if planted closely. Cabbages and turnips can be interplanted to increase yields by complementing each other with their shape and growth habit form. Lettuce seed casted around a row of carrots can be harvested throughout the season without harming the carrots below. Pole beans and low-sprawling squash can be planted in the same hill, one goes up a long pole and the other slithers outward along the ground—just be sure to set a few flagstones down so you have a place to step.

Permaculture

Plants that live in one spot and are cared for with that in mind, that’s permaculture. Some take it further in a back-to-the-land, off-the-grid way of life kind of way. At the heart of permaculture dwells sustainable architecture, aquaponics, personal and shared philosophy, horticulture, and overly charismatic people. The term and way of life it describes can mean something vastly different from one individual to the next. Permaculture is all these things and more. It’s difficult to capture what it means in a brief, neat descriptive statement.

The first step to permaculture on your property is to understand the little ecosystem that exists in your garden. The second step is to promote it. Your plan must rely on sustainable and self-sufficient ideals. Permaculture can provide ample food and beauty in your yard, it just takes a bit more work to setup but over time will take less time as it becomes a more closed and sustainable system.

Permaculture Links:

- Tips for designing your permaculture heaven

- Understanding the meaning and elements of permaculture

- Current events, news and ongoing research on permaculture

I’ve gone so far as to compost my own poop from a composting bucket style outhouse to mix in with chicken manure. Since I’ve moved and updated a to toilet—which I must say is much warmer in winter. We collect our own rainwater for our animals, use all of their waste right here in various applications. A window from a sliding glass door is the roof for three of our animal houses here. This collects solar energy and heats our animals in the depth of winter.

The chicken and rabbit manure is mixed with sawdust and within a month’s time a 3 x 4′ wire compost pod reaches 80°f in the center. Our hot compost is poured into a rectangular hole cut in the sod on the front lawn with a thick layer of leaf matter lining the bottom. A layer of metal mesh with 1/2″ holes is set over the compost. A layer of soil over that. In the soil grows cold season crops that use the heat and gas to thrive all winter. Over the top of this mess lies a double paned vinyl sliding glass door panel that was free on the side of the road this past spring. The food grown inside goes back to feed the rabbits and poultry. This is just one example of a closed loop system here on the homestead.

Vertical Planting

Many plants you think of as bush or ground vines can be either trellised. Some bush plants can be found in tall growing vine varieties. This not only saves space, but gives a your garden a modern and decorative twist. Peas, cucumbers and squash can go vertical. These less common varieties like Telephone Pea and Japanese Climbing Cucumber willingly and vigorously climb to heights of ten feet or more.

Just because these are soft, herbaceous plants doesn’t mean they cannot be pruned. Careful, well thought pruning before flowering in the first few feet of growth is most effective. If you wait too long it’s likely to impact your harvest. Don’t allow the vines to choke each other out, they will need plenty of space and not be shading each other. Promote stronger vines to go straight up and either reroute or snip off lesser, downward reaching vines. Vines like these will snap easy, so use minimal pressure when handling and tying them. An old rag can be cut into thin strips, preferably a stretchy one, and used to tie the vine off loosely and allow it to reattach itself where you want it to be.

Snipping off small shoots early promotes growth in others nearby because the resources are now available to stir new growth elsewhere and quickly take action to make up for it’s loss. Only a few ought to need snipping per plant and most ought to be tied off, rerouted and watched. Once the main shoot is quite long (three to five feet depending on your plant species) and headed in the right direction, promote the side shoots to lightly cover the area without fighting for sunlight. Think of this as your calming activity instead of a chore. It’s a therapeutic vine bonsai to mellow you out every few days.

Space savers for urban planting

If you have a very limited amount of space there are many things to consider to get the most out of your garden. Depending on how urban you are growing, you may need to plant a lot of pollinator attractants to ensure the pollination of your crop. In urban areas there is a higher chance of a cat digging up your hard work to use your soft garden bed as it’s litter box. Passing dogs may cock to water your plants too. If these issues seem inevitable, use preventative measures to ward off these nuisances.

A short fence does wonders. Even a wire decorative edging fence can be all it takes to keep them out. If you want to go all out, you could set up a motion sensor sprinkler to scare the heck out of digging cats. In the end a small gated garden or raised beds on little legs might be most suitable depending on how persistent these issues are for your individual garden plot.

Taller welded wire fencing will keep out many critter who will eat, tamper with or simply dig up your crop. This type of fencing can be dual purpose for as a trellis and barrier. If you’re not worried about animals eating your crops, then use the fencing as a support for climbers like cukes, peas and beans. Don’t underestimate their height. A rope can be run to a nearby structure for them to climb or sturdy sticks can be quickly tied to the fencing to poke up over the top.

Raised beds can be at different levels. Ones built on legs are easier for the elderly, simple to care for and can be moved in the off season. The downside it they are temporary structures and cannot be easily made to extend the season as they will stay the temperature of the air, not the soil. This makes them more susceptible to frost. Another downside is they will evaporate water more quickly. Unfortunately, planning a garden for Maine’s climate generally does not include these short-term table box style beds unless they are an edition to in-ground plots or an extension of the larger garden.

Sweet Summer

Second Seedings & Transplanting Mid-season

Once an early harvest crop leaves a spot open another can take its place. Make sure it has plenty of nutrients left in the soil by mulching with fine grain compost for seeds or sprouts. Larger plants can be moved from another spot where they don’t have enough room. You might also keep more transplants in a coldframe or your home for second plantings. Mulch them with a thick layer of larger compost matter.

Weeding

Weeds suck up the good stuff and steel it from your beloved veggies! Stop these heathens by pulling them up by the root, cutting them down with a how, tilling them every Sunday afternoon with your Mantis—just don’t let them take over. The earlier in the season you declare a war on weeds the better off your garden will be. Some weeds can be nice for your garden and left to attract insects and can be stepped on without concern in the row. Clover attracts insects and is in the pea family, so it pulls nitrogen into the soil making it available for use by your garden plants. Just don’t let it get too cozy and take the place over.

Lambsquarter are a very common potable herb that is comparable to spinach that I see folks rip out all the time to make room for planting spinach—no joke. Humans produce fourteen essential amino acids. Eight of them must be consumed in external sources—one great and simple source is lambsquarter.

Each lambsquarter leaf has a dusty layer of mineral salts from the soil—a key indicator of its mineral value. This potable herb can be used as a salt replacement in stir fries, soups and meat pies. Leaves from this plant can be hung to dry, crushed and mixed with other spices for a salty spice mix to use as a chicken rub or stew seasoning.

The moral of my meandering story is to be careful of what you pull up when weeding your garden. Think about the system as a whole and why you have the garden to begin with. If perfectly straight rows and tilled foot paths are really important to you, then make it so—just know that there is much more to a garden then beauty alone. Upon taking a closer look you might begin wild food foraging in your weedy rows. Planning a garden for Maine’s climate means thinking about it all winter and enjoying it to the fullest while it’s green.

Preventing Weeds

You can lay stuff down to prevent weeds but it comes at a cost. Weed barriers can block air and water from entering the surrounding soil and kill the microorganisms that keep your soil productive. Slugs enjoy living under boards, plastic and fabric. Black liners can make the ground hotter than normal and speed up decay and other biologic processes in the soil that will eat up available nutrients rapidly. My solution is mulching with great compost.

Using compost to keep the weeds at bay is a win-win. Macronutrients are delivered to the plants as compost decays on the surface. Rain or occasional watering percolates the amazing compost tea down to thirsty roots. Careful not to overwater your plants, because the good stuff will run off instead of going into the soil below. Use a thick layer but don’t suffocate your plant stems or roots—except for tomatoes, they LOVE that and will send out adventitious roots from the stem. When planning a garden for Maine’s climate one must consider the wacky, ever changing weather. When rain does not come for a week, your plant roots will remain moist with a liberal layer of compost over them.

Coping with Garden Pests and Diseases

First of all, if you see a pest in action—squash it. Don’t just stand there in awkward silence watching it munch your valuables. This is not something I’m amazing at yet but I’m happy to share the following resources I use as a reference when my garden is micro-invaded. For information on common Maine garden pests at the University of Maine’s Co-op page for Pest ID. Or for a full list organized by vegetable, with additional information on other plant problems, see this insect pest and disease management website full of detailed photos to help identify your plant’s ailment.

For larger mammal-type invitations I have much more expertise.

Deer Repellent

The best defence against deer is a tall, sturdy fence. If you cannot have a fence ,they are hopping over it, reaching through it or treating your flower boxes like a salad bar—then use this stuff.

Mix the following in a 1-gallon tank sprayer:

- 2 beaten eggs, strain to remove junk that will plug sprayer

- 1 cup milk, yogurt, buttermilk or sour milk

- 2 tablespoons cayenne pepper

- 10 drops essential oil of cinnamon

- 10 drops essential oil of eucalyptus

- 1 tablespoon cooking oil

- 1 tablespoon liquid dish soap

Top off the tank with water and pump it up. Shake the sprayer occasionally while applying. Mist onto dry foliage. One application will last for 2 to 4 weeks in dry weather and should be reapplied following rain once the leaves have had time to dry. There are regulations that allow for farming operations and gardeners to obtain special permits to shoot problem deer. This is a great way to put healthy, lean meat on the table and reduce pest impact on your garden. You could also invite hunters over in fall.

Mole Repellent

This simple three-ingredient spray-on soil repeller works for a month or more depending on rainfall and foot traffic on the treated area. There are always mouse traps too, set them at a tunnel opening and check them daily. Don’t let the cat step in them—ouch! I use them, but set them off when the cat goes in the garden with me (it’s fenced off unless I let him in). If a mole or mouse is caught, put in in the compost to make it into garden fertilizer. Everything has a use.

- 1/4 cup unrefined castor oil (available at most pharmacies.)

- 2 tablespoons dishwashing liquid

- 6 tablespoons water

Combine oil and dishwashing liquid in a blender until well combined then the water and blend for about the same amount of time. This is a concentrated blend made to mix a ratio of 2 tablespoons repellent solution with 1 gallon of water. A watering can or sprayer can be used to deter moles, voles and mice from entering your garden.

This amount treats 300 square feet. In spring, walk the outside of the garden with this solution to deter them from ever entering. If this is for an active mole issue rather than a preventive barrier liberally apply it to soil surrounding mole tunnels. Spray the entire area needing protection, as moles will burrow under a perimeter treatment.

Early Fall

Cloches to Extend the Season

A cloche is a bell-shaped or half-circle covering made of glass or plastic that is set over a plant to provide similar protection as row covers. Cloches can be simply made by using 1-liter plastic bottles or used milk jugs. Cut out the bottom, press the cut edge into the soil around the plant, and remove the cap to allow venting.

Harvest

Canning

Freezing

Fresh Storage

Late Fall

Cover Crops

Extending the Season

Insulating Beds

Collecting Fallen Needles and Leaves

Pruning

Transplanting

Planting Trees

Early Winter

Tending Cold Frame Beds

Deep Winter

Planning for The Next Season

Keeping Snow Clear of Protected Beds

Enjoying the Bounty from Last Year’s Crop